Git stores everything in its database not by file name but by the hash value of its contents.

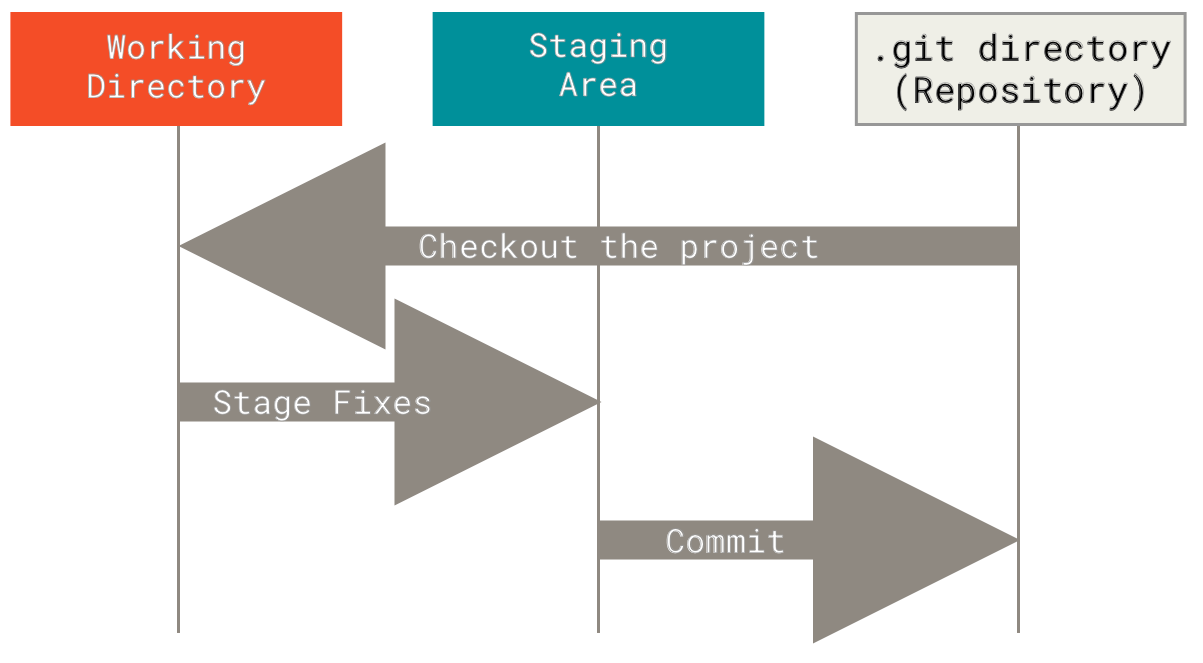

**Three states of GIT: ** modified, staged and committed

modifiedmeans that you’ve changed the file but have not committed it to your database yet.stagedmeans that you have marked a modified file in its current version.committedmeans that the data is safely stored in your local database.

Git’s workflow:

- You modify files in your working tree.

- You selectively stage just those changes you want to be part of your next commit, which adds only those changes to the staging area.

- You do a commit, which takes the files as they are in the staging area and stores that snapshot permanently to your Git directory.

Installing Git

-

On Linux

If you’re on Fedora (or any closely-related RPM-based distribution, such as RHEL or CentOS), you can use

dnf:1

$ sudo dnf install git-all

If you’re on a Debian-based distribution, such as Ubuntu, try

apt:1

$ sudo apt install git-all

-

On Windows

Just go to https://git-scm.com/download/win and the download will start automatically.

Configuration

Git comes with a tool called git config that lets you get and set configuration variables that control all aspects of how Git looks and operates.

| Variable | works for |

|---|---|

/etc/gitconfig file |

every user on the system |

.gitconfig or ~/.config/git/config |

the user |

config file in the Git directory (that is, .git/config) of whatever repository you’re currently using |

the repository |

Each level overrides values in the previous level.

-

user information

1 2

$ git config --global user.name "John Doe" $ git config --global user.email johndoe@example.com

You need to do this only once if you pass the

--globaloption, because then Git will always use that information for anything you do on that system.If you want to override this with a different name or email address for specific projects, you can run the command **without the

--global**option when you’re in that project. -

checking your settings

1 2 3 4

$ git config --list $ git config <key> $ git config user.name

-

getting help

1 2 3 4 5 6

$ git help <verb> $ git <verb> --help $ git <verb> -h(more concise) $ man git-<verb> $ git help config

Git Basics

-

Initializing a repository

1

$ git init -

Cloning a existing repository

1

$ git clone [url] (repository name)

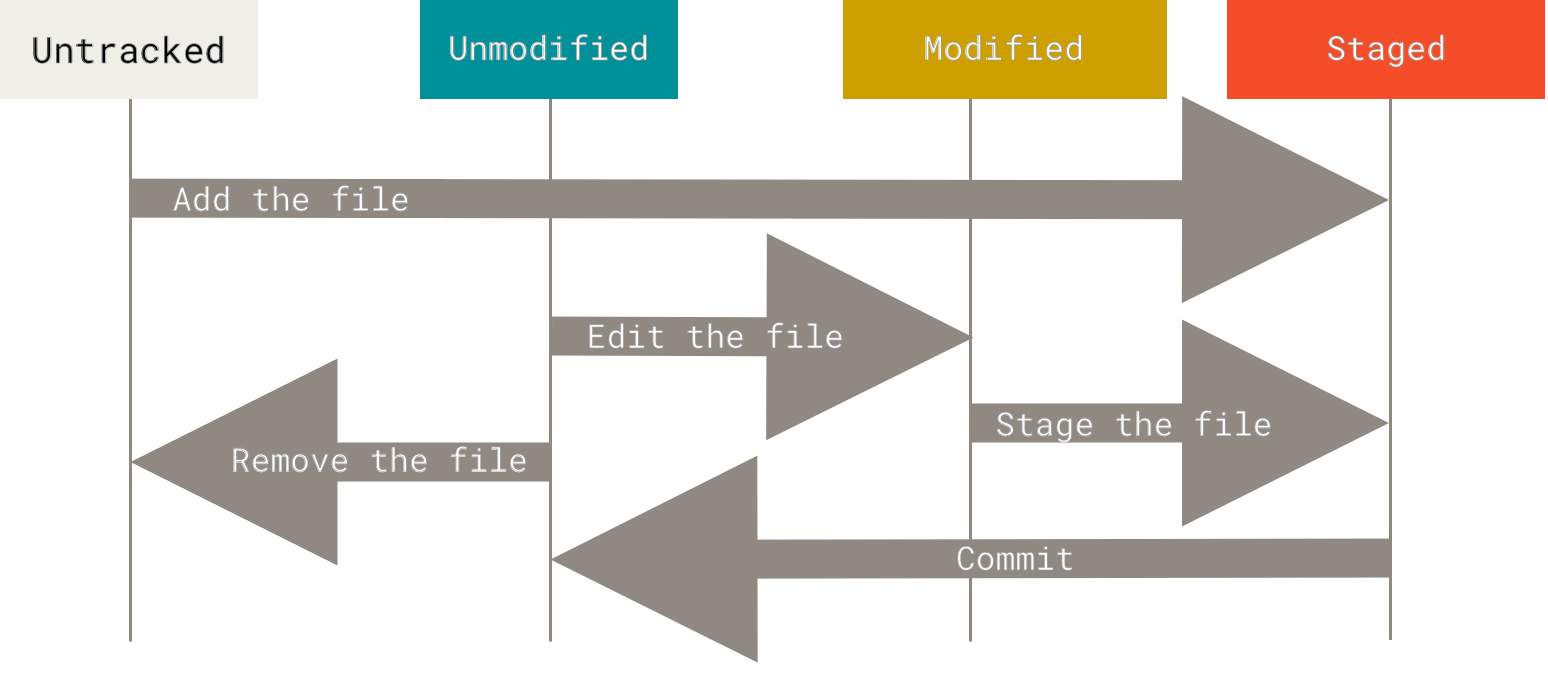

Each file in your working directory can be in one of two states: tracked or untracked.

-

Tracked files are files that were in the last snapshot

-

Untracked files are everything else. Git won’t start including it in your commit snapshots until you explicitly tell it to do so.

Recording Changes

Checking the status: git status

1

$ git status

If you run this command directly after a clone:

1

2

3

On branch master

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'.

nothing to commit, working directory clean

If you add a new file named README:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

On branch master

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'.

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

README

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

Tracking, Staging: git add

-

Tracking new files

1

$ git add README1 2 3 4 5 6 7

$ git status On branch master Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'. Changes to be committed: (use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage) new file: README

-

Staging modified files

If you change a previously tracked file called CONTRIBUTING.md

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

$ git status On branch master Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'. Changes to be committed: (use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage) new file: README Changes not staged for commit: (use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed) (use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory) modified: CONTRIBUTING.md

git addis a multipurpose command — you use it to begin tracking new files, to stage files, and to do other things like marking merge-conflicted files as resolved.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

$ git add CONTRIBUTING.md $ git status On branch master Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'. Changes to be committed: (use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage) new file: README modified: CONTRIBUTING.md

If you change once again the file CONTRIBUTING.md

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

$ vim CONTRIBUTING.md $ git status On branch master Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'. Changes to be committed: (use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage) new file: README modified: CONTRIBUTING.md Changes not staged for commit: (use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed) (use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory) modified: CONTRIBUTING.md

Now

CONTRIBUTING.mdis listed as both staged and unstaged.If you modify a file after you run

git add, you have to rungit addagain to stage the latest version of the file:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

$ git add CONTRIBUTING.md $ git status On branch master Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'. Changes to be committed: (use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage) new file: README modified: CONTRIBUTING.md

-

Short status

1 2 3 4 5 6

$ git status -s M README #Modified not yet staged MM Rakefile #Modified, staged then modified again A lib/git.rb #new file, staged M lib/simplegit.rb #Modified, staged ?? LICENSE.txt #new file, untracked

Those who will be committed are the files which have a A or M on the left-hand column and nothing on the right-hand column.

Ignoring files: .gitignore

The rules for the patterns you can put in the .gitignore file are as follows:

- Blank lines or lines starting with

#are ignored. - Standard glob patterns work, and will be applied recursively throughout the entire working tree.

- You can start patterns with a forward slash (

/) to avoid recursivity. - You can end patterns with a forward slash (

/) to specify a directory. - You can negate a pattern by starting it with an exclamation point (

!).

Glob pattern syntax:

| Wildcard | Description | Example | Matches | Does not match |

|---|---|---|---|---|

* |

matches any number of any characters including none | Law* |

Law, Laws, or Lawyer |

GrokLaw, La, or aw |

*Law* |

Law, GrokLaw, or Lawyer. |

La, or aw |

||

? |

matches any single character | ?at |

Cat, cat, Bat or bat |

at |

[abc] |

matches one character given in the bracket | [CB]at |

Cat or Bat |

cat or bat |

[a-z] |

matches one character from the (locale-dependent) range given in the bracket | Letter[0-9] |

Letter0, Letter1, Letter2 up to Letter9 |

Letters, Letter or Letter10 |

!! You can also use two asterisks to match nested directories; a/**/z would match a/z, a/b/z, a/b/c/z

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

# ignore all .a files

*.a

# but do track lib.a, even though you're ignoring .a files above

!lib.a

# only ignore the TODO file in the current directory, not subdir/TODO

/TODO

# ignore all files in any directory named build

build/

# ignore doc/notes.txt, but not doc/server/arch.txt

doc/*.txt

# ignore all .pdf files in the doc/.../directory

doc/**/*.pdf

To check: https://github.com/github/gitignore

Viewing changes: git diff

-

unstaged ones

git diffgit diffby itself doesn’t show all changes made since your last commit — only changes that are still unstaged. -

staged ones

git diff --staged

Committing changes: git commit

1

2

$ git commit # the editor will be launched

$ git commit -m # with a commit message

1

2

3

4

[master (root-commit) 35c838c] first commit

2 files changed, 3 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 CONTRIBUTING.txt

create mode 100644 README.txt

! Skipping the staging step with -a:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

$ git status

On branch master

Your branch is up-to-date with 'origin/master'.

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: CONTRIBUTING.md

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

$ git commit -a -m 'added new benchmarks'

[master 83e38c7] added new benchmarks

1 file changed, 5 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

! Redoing the commit with --amend

1

2

3

$ git commit -m 'initial commit'

$ git add forgotten_file

$ git commit --amend

Removing changes: git rm

-

git rm [file]: Removing a file, it will not be in the tracked files’ list -

git rm -f [file]: Removing a modified then staged file-fstands for force. This is a safety feature to prevent accidental removal of data that hasn’t yet been recorded in a snapshot and that can’t be recovered from Git. -

git rm --cached [file]: Removing a file from staging area but keep it in your work tree

! **If you simply remove the file from your working directory, it shows up under the **“Changes not staged for commit” (that is, unstaged) area of your git status output

Moving a file: git mv

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

$ git mv README.md README

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

renamed: README.md -> README

is equivalent to:

1

2

3

$ mv README.md README

$ git rm README.md

$ git add README

Viewing the commit history: git log

| Option | Description |

|---|---|

-p |

Show the patch introduced with each commit. |

--stat |

Show statistics for files modified in each commit. |

--shortstat |

Display only the changed/insertions/deletions line from the –stat command. |

--name-only |

Show the list of files modified after the commit information. |

--name-status |

Show the list of files affected with added/modified/deleted information as well. |

--abbrev-commit |

Show only the first few characters of the SHA-1 checksum instead of all 40. |

--relative-date |

Display the date in a relative format (e.g. “2 weeks ago”) |

--graph |

Display an ASCII graph of the branch and merge history beside the log output. |

--pretty |

oneline, short, full, fuller, and format |

--oneline |

Shorthand for --pretty=oneline --abbrev-commit used together. |

Useful options for –pretty=format:

| Option | Description of Output |

|---|---|

%H |

Commit hash |

%h |

Abbreviated commit hash |

%T |

Tree hash |

%t |

Abbreviated tree hash |

%P |

Parent hashes |

%p |

Abbreviated parent hashes |

%an |

Author name |

%ae |

Author email |

%ad |

Author date (format respects the –date=option) |

%ar |

Author date, relative |

%cn |

Committer name |

%ce |

Committer email |

%cd |

Committer date |

%cr |

Committer date, relative |

%s |

Subject |

Options to limit the output of git log

| Option | Description |

|---|---|

- |

Show only the last n commits |

--since, --after |

Limit the commits to those made after the specified date. |

--until, --before |

Limit the commits to those made before the specified date. |

--author |

Only show commits in which the author entry matches the specified string. |

--committer |

Only show commits in which the committer entry matches the specified string. |

--grep |

Only show commits with a commit message containing the string |

-S |

Only show commits adding or removing code matching the string |

Undoing things

-

Unstaging a staged file

1 2 3

$ git restore --staged <FILE> #same as $ git reset HEAD -- <FILE>

-

Unmodifying a modified file

1 2 3

$ git restore <FILE> #same as $ git checkout -- <FILE>

! It’s important to understand that

git checkout --is a dangerous command. Any local changes you made to that file are gone — Git just replaced that file with the most recently-committed version. Don’t ever use this command unless you absolutely know that you don’t want those unsaved local changes.

Remotes

-

Adding a remote:

git remote add <shortname> <URL> -

Listing your remotes:

1 2

$ git remote $ git remote -v #showing the URLs

-

Renaming:

git remote rename <name> <newname> -

Removing:

git remote remove <name> -

Inspecting:

git remote show <name> -

Fetching and Pulling from your remotes:

1 2

$ git fetch <remote> $ git pull <remote>

Attention:

- If you clone a repository, the command automatically adds that remote repository under the name “origin”.

- the

git clonecommand automatically sets up your local master branch to track the remote master branch (or whatever the default branch is called) on the server you cloned from. - git pull = git fetch + git merge

-

Pushing to your remotes:

1

$ git push <remote> <branch>

Tagging

1

2

$ git tag <tagname> #lightweight

$ git tag -a <tagname> -m <message> #annotated

-

Listing:

git tag -

Inspecting:

git show <tagnme> -

Tag latter:

git tag <tagname> <checksum> -

Sharing tags:

1 2

$ git push <remote> <tagname> #sharing a certain tag $ git push <remote> --tags #sharing all tags

-

Deleting a tag:

git tag -d <tagname>Note that this does not remove the tag from any remote servers.

1

$ git push origin --delete <tagname>

Branching

Local branches

-

Listing branches:

git branch1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

# to see the last commit on each branch $ git branch -v # to see all tracking branches # It’s important to note that these numbers are only since the last time you fetched from each server.(last fetch) $ git branch -vv # those that you have merged into the current branch $ git branch --merged # those that you have not yet merged into the current branch $ git branch --no-merged

-

Creating a branch:

git branch <branch name> -

Switching to a branch:

git checkout <branch name> -

Switching while creating a branch

1 2

$ git checkout -b <branch name> $ git checkout -b <branch name> <remote>/<remote branch>

-

Merging a branch into the current one:

git merge <branch name> -

Deleting a branch

1 2 3 4

# deleting a merged branch $ git branch -d <branch name> # deleting a unmerged branch $ git branch -D <branch name>

Remote branches

Remote-tracking branches are references to the state of remote branches.

Remote-tracking branch names take the form <remote>/<branch>.

Git’s clone command automatically names it origin for you, pulls down all its data, creates a pointer to where its master branch is, and names it origin/master locally. Git also gives you your own local master branch starting at the same place as origin’s master branch.

-

Updating remote-tracking branches:

git fetch <remote>This command looks up which server “origin” is (in this case, it’s

git.ourcompany.com), fetches any data from it that you don’t yet have, and updates your local database, moving yourorigin/masterpointer to its new, more up-to-date position. -

Pushing

Your local branches aren’t automatically synchronized to the remotes you write to — you have to explicitly push the branches you want to share.

1 2 3

$ git push <remote> <branch> # Git automatically expands the serverfix branchname out to refs/heads/serverfix:refs/heads/serverfix, which means, “Take my serverfix local branch and push it to update the remote’s serverfix branch.” $ git push <remote> <local branch>:<remote branch>

! Note that when you do a fetch that brings down new remote-tracking branches, you don’t automatically have local, editable copies of them. In other words, in this case, you don’t have a new

serverfixbranch — you have only anorigin/serverfixpointer that you can’t modify. -

Tracking branches

When you clone a repository, it generally automatically creates a

masterbranch that tracksorigin/master.However, you can set up other tracking branches if you wish

-

Same name

1 2 3

$ git checkout --track <remote>/<branch> # is equivalent to $ git checkout -b <branch> <remote>/<branch>

-

Different name

1

$ git checkout -b <local branch> <remote>/<remote branch>

-

Existing local branch

1

$ git branch -u <remote>/<branch>

-

-

Deleting remote branch:

git push <remote> --delete <branch>

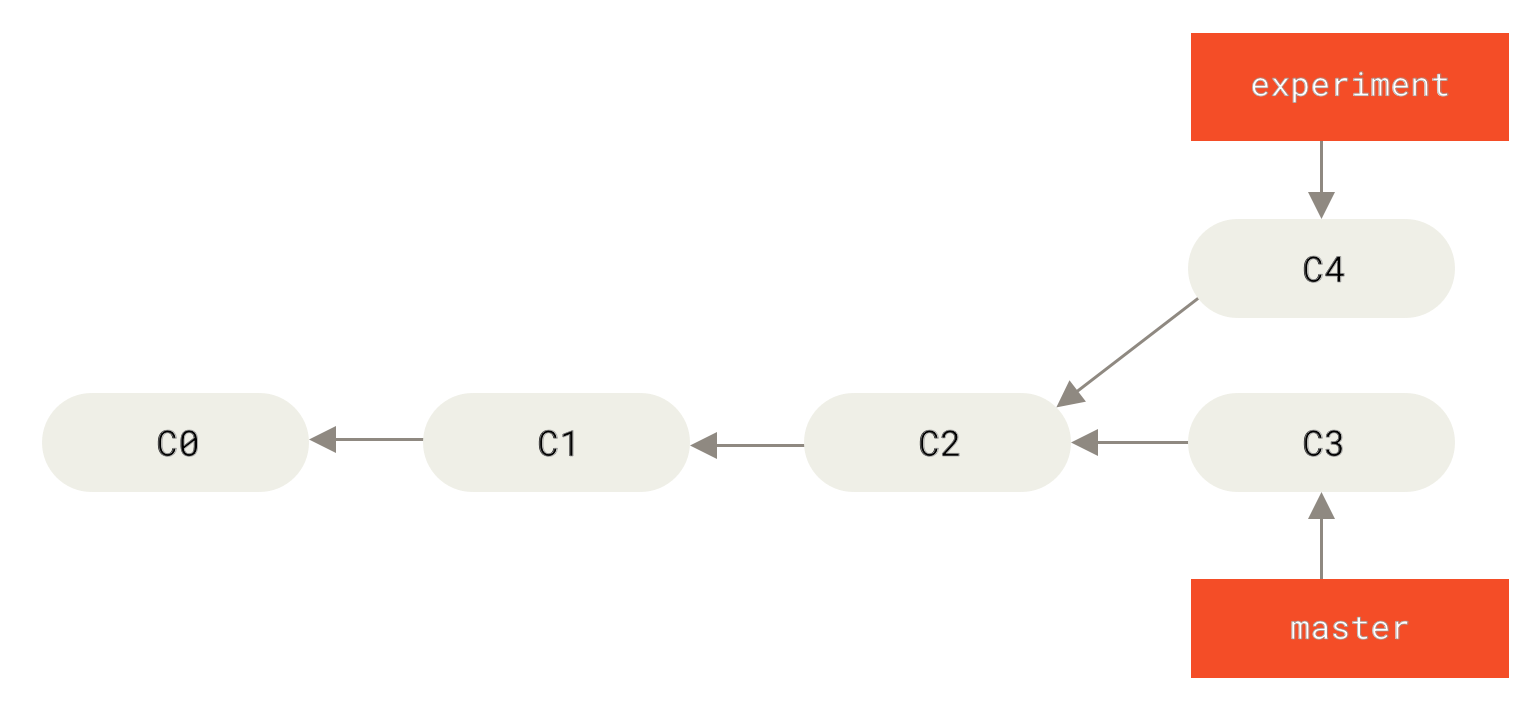

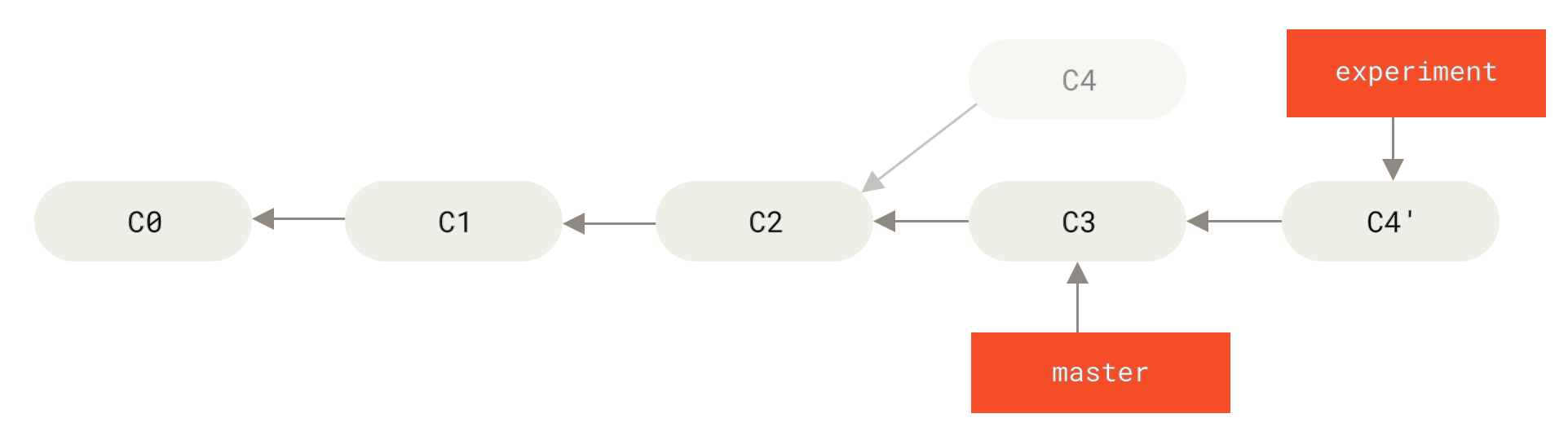

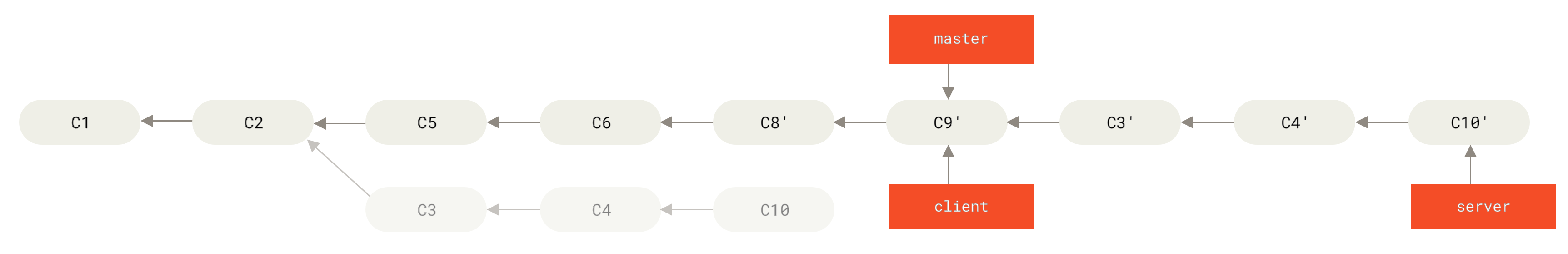

Rebasing

Do not rebase commits that exist outside your repository and people may have based work on them.

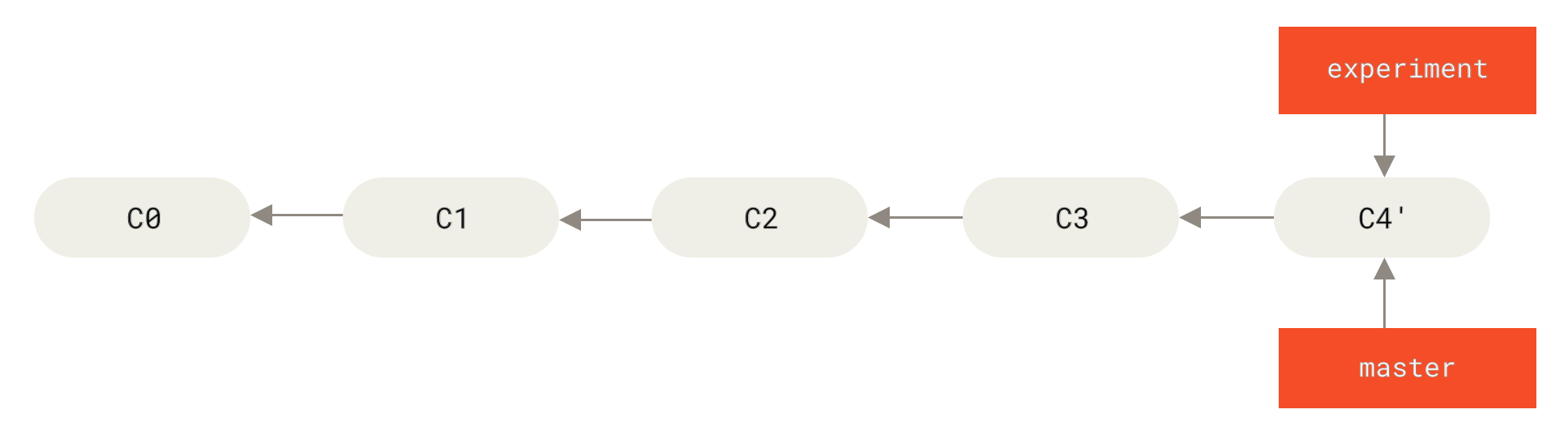

Example 1

1

2

$ git checkout experiment

$ git rebase master

1

2

$ git checkout master

$ git merge experiment

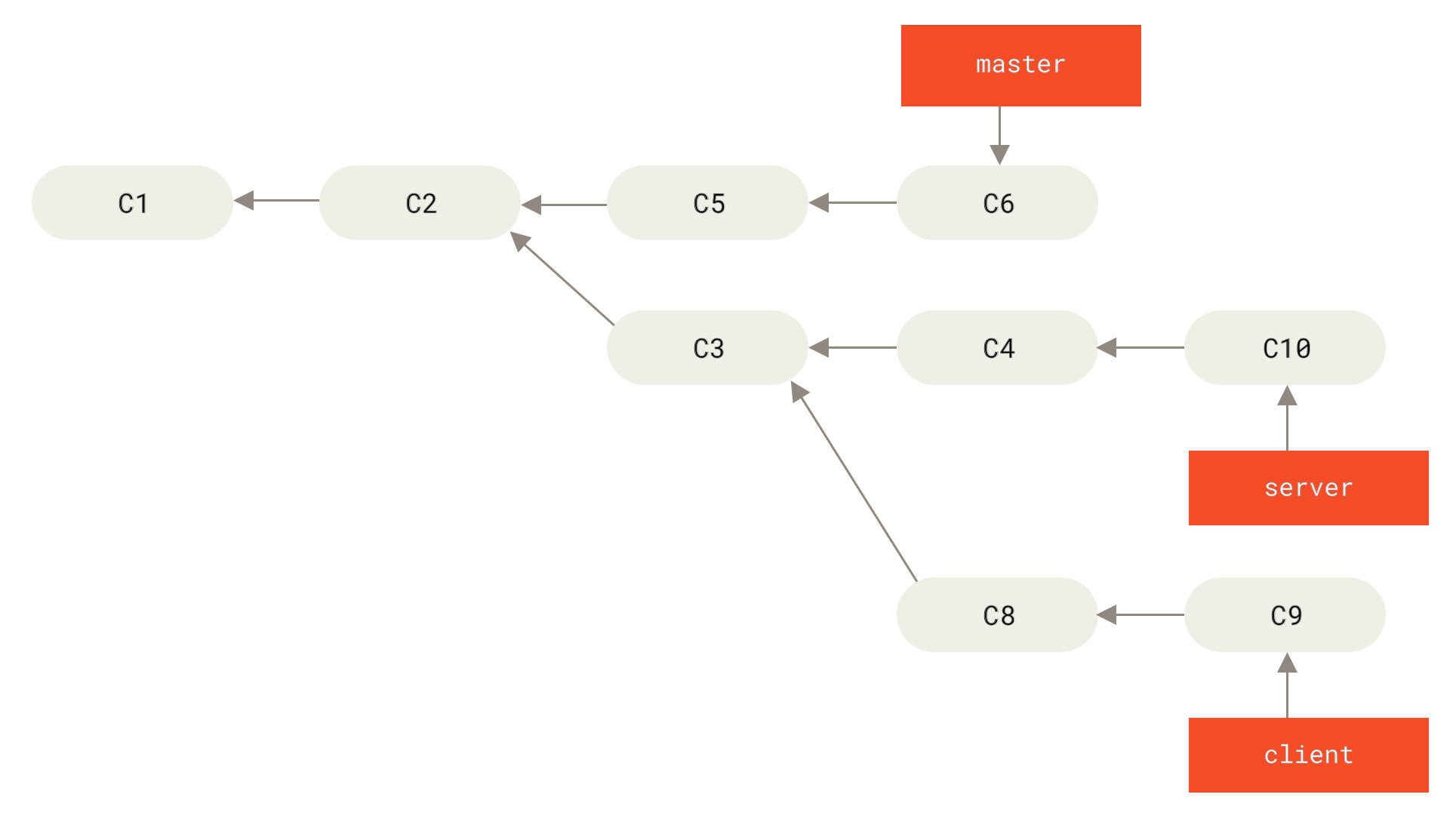

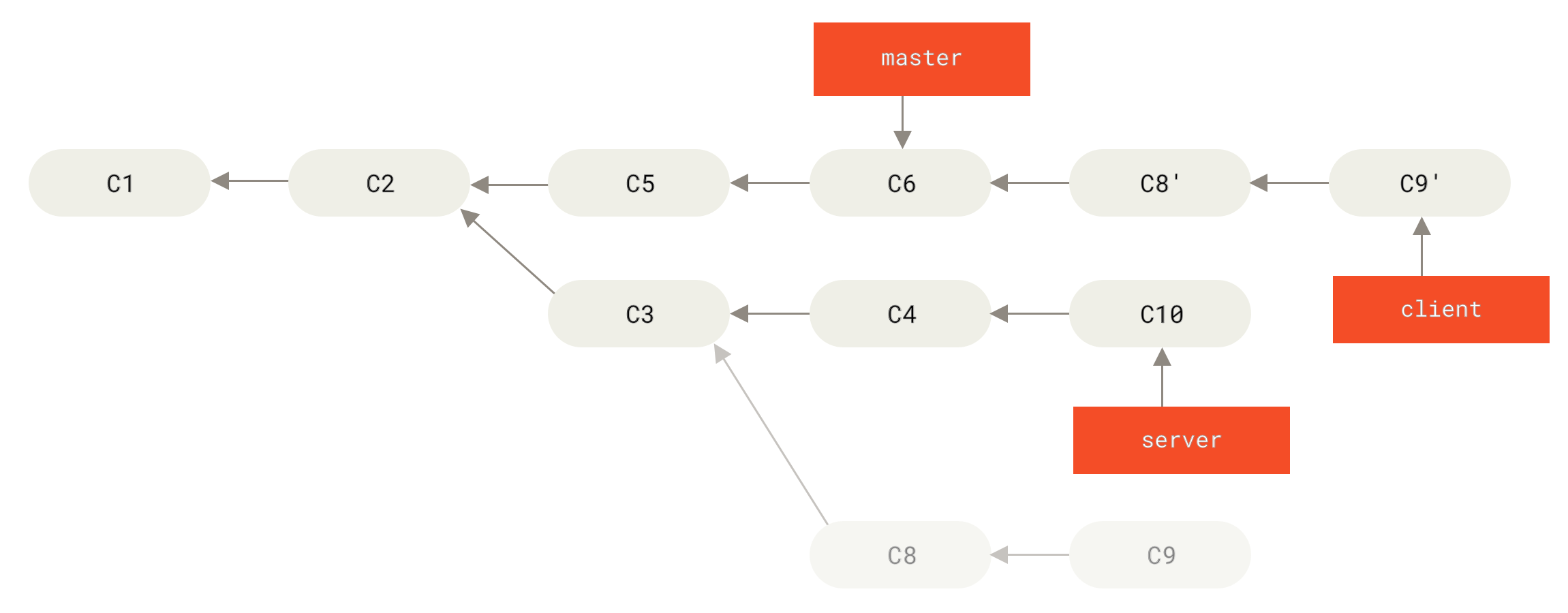

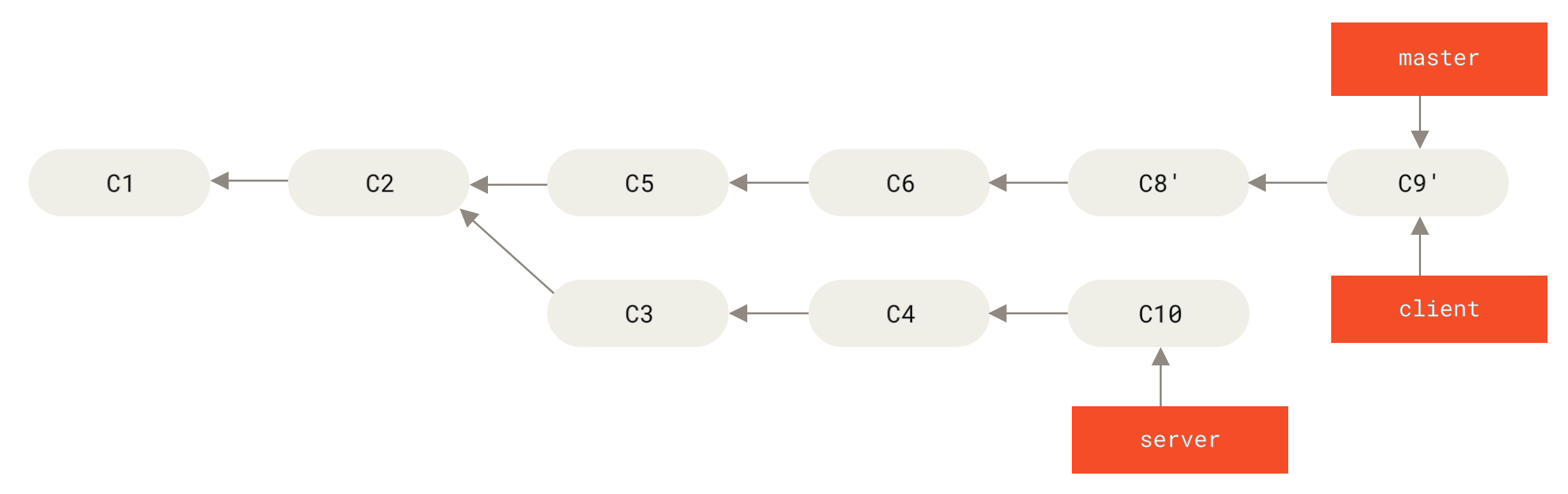

Example 2

1

$ git rebase --onto master server client

1

2

$ git checkout master

$ git merge client

1

2

3

# git rebase <basebranch> <topicbranch>

# rebase the server branch onto the master branch without having to check it out first

$ git rebase master server

Annex

Alias

-

1

$ git config --global alias.unstage 'reset HEAD --'

-

1

$ git config --global alias.last 'log -1 HEAD'